The Springwell Pit Disaster by M. Peel

Springwell Pit Disaster

Friday 6 December 1872

By Malcolm Peel

1872 was a memorable year in Dawley mining history: The Springwell Pit disaster when eight young men, employed by the Coalbrookdale Company, who all came from the Dawley area, lost their lives. The disaster affected local people greatly as it was their first major disaster in Dawley, although nine men and three boys had been killed at The Dark Lane Pit in 1862. The Springwell disaster followed hot on the heels of the Pelsall disaster which had occurred on November 14th the same year; killing 22 men including 5 from Dawley.

The eight men died when the chain at the ironstone pit on which they were being hauled to the surface snapped and they were plunged to their deaths in the mine 150 yards below the surface. At four thirty in the afternoon at the end of their shift as usual a group of eight young men attached themselves to the triple linked chain which rose 50 yards from the floor of the mine before the links snapped. Seven men died where they fell and an eighth died soon after he was brought to the surface.

Their bodies were taken to the Crown Inn, Little Dawley to be laid out and identified.

They were:

Isaiah Skelton, whose reported age was 15 but who was actually only 14years old a miner from Little Dawley

Robert Smith aged 18 a miner from Holly Hedge

John Davies aged 19 a filler from Brandlee

Allen Wyke aged 20 a miner from the Finney

John Yale aged 21 a miner from Dawley

Edward Jones aged 21 a miner from the Stocking

William Bailey aged 21 a miner from the Finney

John Parker aged 22 a miner from Holly Edge

Springwell Pit Communal Grave, Holy Trinity churchyard

All men were single except William Bailey who was married with a child. The men’s funeral was held in Holy Trinity Church the following Tuesday afternoon – 10th December. Long before the time set for the funeral thousands had flocked into Little Dawley. The whole greater Dawley area was in mourning for the eight men who lost their lives. It was estimated that there were at least 10,000 people come to pay their respects such was the enormity of the tragedy.

The inquest that followed the tragedy found that ‘the deceased were killed by the breaking of a chain’. William Heighway (the Coalbrookdale Company’s engineer) and Henry Rawson (the Company’s overall pit manager) were highly criticised by both the coroner and the jury. The coroner said to Heighway, ‘You systematically neglected your duties.’ To Rawson he said, ‘ A joint responsibility rests upon you.’ However, no criminal charges were brought against either man or the Coalbrookdale Company.

The pit at which the accident occurred was part of the Top Yard Colliery situated in Holly Lane Little Dawley. The winding operation, here, was relatively slow when compared to cage winding. The Dark Lane Pit, (mentioned above) was probably the first pit in the coalfield to use cages, and was sometimes called “The Cage Pit”, and on other occasions, called “Flies pit” due to the speed of winding.

At most pits in the area, as was the case here at Springwell, to wind men through a shaft, they attached to the end of the triple linked chin, a short length of chain to which was attached about eight loops of chain. This device was called “The Doubles” and the men would sit in the loops. Sometimes children would sit on the older men’s laps. They did not wear helmets, only cloth caps and they would carry their candles with them.

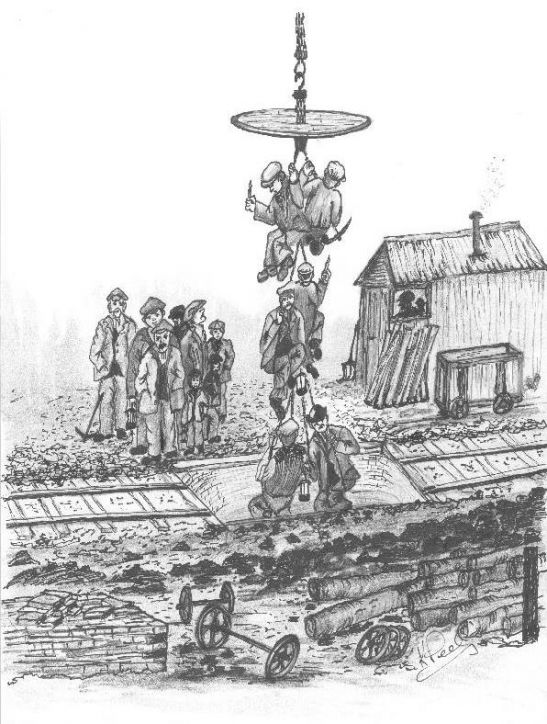

Sketch of men riding the chain

An illustration of the method adopted locally and at the Springwell Pit, the ‘doubles’ shows a number of chain loops in which the men sat. The round wooden board, called a “bonnet”, is attached to the triple link chain was to provide protection from objects falling down the shaft, and the group of men suspended below it were called a ‘bond’.

The workers earlier that week had mentioned the poor condition of the triple link chain, which consisted of three lengths of chain with wooden wedges to stop the chains from twisting, and indeed some replacement of rivets had supposedly taken place. However, a spare chain which had been purchased previously was not fitted and the men had been lowered down with some trepidation only to have the tragedy occur on their ascent.

Work resumed at the mine the following day and the mine continued to be worked until about 1880.